“A Public View of a Bronx Life”

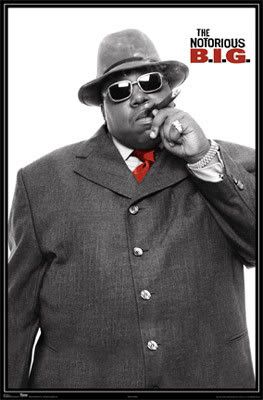

Allen Jones and Mark Naison’s The Rat That Got Away

“…I stopped by the East Side Center to let PJ know how I was doing, and during the conversation he said to me. ‘I know you don’t tell those white folks where you are from.’”

“Of course, he was wrong about that, but his comment reinforced something I already knew instinctively: how important it is to be proud of where I come from. A lot of black people who cut ties with their past to be accepted in the white world end up belonging nowhere. Though I was no historian, I was becoming a pretty good student of history, and I concluded that without a sense of your past, you can lose yourself. Once I became conscious of this fact, I decided to claim everything I did, for better or for worse, and keep in touch with my street side, even when I was hanging with the rich and famous.

“My conversation with PJ…helped me understand who I was.”

Allen Jones

The Rat That Got Away

Allen Jones’ story is the type of inspirational, “coming of age” account that inner-city teachers, youth workers, and scholars clamor for. From growing up poor in the South Bronx’s Paterson housing projects, Jones finds economic and social success in Europe. A well-known New York City schoolboy street basketball standout, in adulthood he transitions into an accomplished German banker. And after several years as a local drug dealer, and participating in the emerging gangster culture of the late 1960’s, Allen shifts his attention back to the moral foundations that were central to his childhood: family and church. The events of Allen Jones’ life point to redemptive possibilities that can be achieved in spite of early life mistakes and obstacles. In this way, knowing who he is, can help today’s young people know who they can be.

But the totality of Jones’ years is more than a collection of life lessons which end result is an interesting memoir and a cautionary tale. The Rat That Got Away provides a narrative with a richer historical lens, and a deeper social meaning than pure “factoids” can provide. Emanating from the Bronx African American History Project's oral history research, Naison and Jones provide an account which is historically true but also intensely personal. The elements that make his memoir so powerful are the poignancy of his experiences and the complexity of his journey. What we learn about the South Bronx and its residents is powerful.

Allen Jones’ life in the projects dramatically alters the standard perception of public housing. The projects have become synonymous with the concept of urban decay, and its residents with the underclass—with both placing the blame on the people in public housing for the literal and figurative deterioration of its space into “ghettos.” The South Bronx, who according to Jill Jonnes’ South Bronx, Rising has the highest concentration of public housing in the United States of America, becomes emblematic of this plight.

The Rat That Got Away successfully resists and complicates that stereotype. Jones’ tells readers of a time when Patterson Projects was a site where families believed they could thrive. The Patterson Community Center, local churches, public schools, and the Police Athletic League ran an assortment of programs that sent kids like Jones “home exhausted” and without “the energy to get into trouble.” A group of mentors and professionals all ran these centers and programs. Most importantly, Jones tells us how these people and institutions were of and for the community; all located either inside or in close proximity to the housing projects, and ran by local residents.

The memoir’s valuable contribution is its insight on how neighborhoods and communities change. Jones life trajectory brings readers through the complicated and tumultuous decade of the 1960’s. Chapters like “The Summer of Unrest: 1964” and “The Streets are Alive: Summer of ‘65” allude to a well-documented time of strife and turmoil the country endured, and Jones’ story tells us how the hardships of the Vietnam War and proliferation of heroin use and sale are among the most devastating hits New York City’s Black and Latino communities take. The 70’s were no different, if not more extreme, as Jones narrates the tragic toll “Bitch Queen Heroin” takes on places like Patterson; and about people being “unable to resist the forces that were tearing apart black neighborhoods in the 70’s.” Most sharp is his observation on the matter: “America was killing us, but we were also killing each other.” Allen’s stories of selling and using drugs attest to this.

But it is here where the book’s strength emanates: the social commentary and personal reflection that accompanies the timeline. Allen Jones provides a memoir which speaks to the particular world-view, political consciousness, and life outlook of a Black man who lived through one of America’s most significant periods. After traveling through several European countries as a professional basketball player, Jones sees the place race occupies in other social environments. Upon his return, he juxtaposes his U.S. life with his Europe experiences, and with brutal honesty shares his thoughts:

“The home I was returning to had treated me, along with all my black brothers and sisters, both living and dead, like slaves, outlaws, second-class citizens, and worse. I knew that part of the reason for this was the history of our country. America had been founded by brutal, self-serving men who were concerned only about gaining wealth and didn’t care how they did it. They killed the Indians for their land and enslaved Africans to help them build their empire, and…I was seeing the long-term effects of what they did…Indians were not even seen in most American cities, and the vast majority of black people, when they were working at all, were doing the lowest-paying jobs. Racism was a way of life in America.”

This is an exemplar of The Rat That Got Away’s shining light: Jones' candor.

This frankness also unveils some of Jones’ shortcomings. When forced to recount his criminal endeavors into drug selling, robbery, and mugging, the author provides detailed reports of his exploits; and we the readers learn of a drug and crime culture very different from that which pervades every aspect of media today. Yet while being so giving of the details to his criminal activity (as should be expected in any memoir building itself as “honest”), Jones does not give us a full account of his personal decision-making process. He recounts how in his childhood peer pressure and the desire to be accepted by older “down brothers” pushed him to mischief and petty crimes. But those choices, and the serious ones that follow, are often clouded and subverted by claims of a “street code:”

“While I can’t defend my actions from that point, I can try to explain what was behind them. My way of thinking had become shaped completely by the street. I knew the rules I was living by and had gotten to the point where I didn’t question them. I knew that Gotham might seem like a high place, but it can become very small when you owe someone money on the streets. And I knew the maxim: ‘You pay or you die.’”

Does the way of the street engulf and envelope a person’s cognitive processes to the point where nothing outside exist? For those who have been completely immersed, bred, and nurtured in this lifestyle, perhaps. But for those, like Allen Jones, who’s frame of reference goes beyond this, and is steeped in parents, Christianity, and a family that taught him “good table manners and basic social graces,” the code of the street explanations are not enough. Much like Malcolm does in his autobiography, or Richard Wright’s depicts through Bigger in Native Son, the decision making process for Black men and their wrong choices have a greater context.

This is where we as scholars, social workers, community organizers, conscientious citizens, and all the sort need to incorporate The Rat That Got Away into our work. The parallels between what faced Allen Jones then and what faces young, poor people of color today are too strikingly similar. How do we cultivate young athletes beyond their physical activities, while also preparing them for their academic and social responsibilities? Can community institutions that train and employ its residents help keep a generation of young people on task and pointed towards success? How can we create organizations and maintain networks that provide assistance, mentorship, and guidance even when adolescents and teenagers stray down the wrong path? And are the prospects for success so dire for Blacks in our current urban landscape that leaving the community where you are from is the only option for success? This memoir gives plenty of fodder for us to delve into these profoundly important and pressing questions.

For these issues are not just important for those looking to “fix the South Bronx.” They are crucial for the creation of a more just, equitable society. Jones’ life gives testament to the redeeming power that determination, perseverance, and repentance can play in navigating through impoverished circumstances; and to the quite vital role that family, mentors, and community institutions play in shaping the lives of young Blacks. But his remarkable individual story is the impetus for questioning why such extraordinary feats are needed for not just success, but for survival; and not for just anybody, but for our society’s most racialized, stigmatized, and marginalized. The Rat That Got Away forces us to think about how to make this American society a more just place.

For about The Rat That Got Away

http://fordhampress.com/detail.html?id=9780823231027

For about Mark Naison's work and the Bronx African American History Project visit:

http://www.fordham.edu/academics/programs_at_fordham_/bronx_african_americ/

and contact: naison@fordham.edu

Michael Partis

michaelpartis@gmail.com

www.michaelpartis.blogspot.com