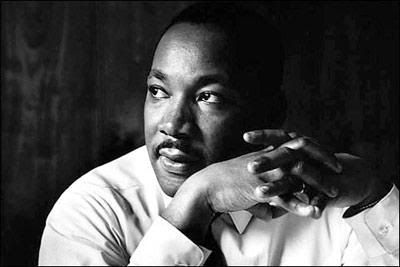

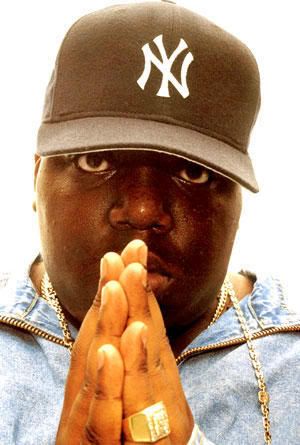

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and The Notorious B.I.G. are two of the biggest cultural figures in American history. Dr. King is renowned for his political, theological, and civic work. Biggie Smalls is celebrated for his exceptional musical ability as a rapper. And both men were vital in two of the 20th century’s greatest social, political, and cultural phenomenons: the Civil Rights Movement, and Hip-Hop.

Yet, we do not think of these men simultaneously. In fact, many might say it is blasphemous to even mention them in the same breath. But as we commemorate Dr. King’s birthday and holiday, and anticipate the release of Notorious (the first major studio film about the life of Biggie), we are afforded a unique opportunity: the chance to bridge generations by carefully looking at two icons. Looking at each man's life allows us to revisit our relationship to them; and to critically think about their virtues and their flaws. Most important though is this question: can we find mutuality and commonality with B.I.G. and King?

Without doubt, the differences between King and Biggie are stark and vast. (Continue below)

Before becoming B.I.G., Christopher Wallace was the son of immigrants and grew up in the urban metropolis of Brooklyn, NY. Thanks to the struggle of his single mother, he did not grow up in abject poverty. Still, Christopher deals with the United States’ harsh truth: educated, poor, affluent, determined, resistant, hard-working, or humble—no matter what your make-up, racism still negatively affects your life-choices. Confronted with this reality, Biggie does was many before, after, and in his generation do: he chooses a life of selling drugs, violence, and crime. It is a life-choice that blurs the line of survival and necessity; of desire and force; of good and bad. To many it is a destructive force that tears apart communities of color. But to Biggie, he was “just trying to make some money to feed my daughter.”

While Dr. King was not able to see the stress, strife, and trauma of the crack epidemic that molded Biggie and the members of his generation, he was intimately familiar with the anger, hostility, and frustration of many in the Black community.

1964-1968 is noted as one of the most tumultuous periods in United States history. While the Civil Rights Movement continued to press on with the hope that faith, civil disobedience, and fortitude would bring equality to America, the racism that produced poverty persisted. These conditions brought many Blacks to “a boiling point.” The frustration turned into two things: political organizing and violence. This was challenging for King and other Civil Rights leaders. They wrestled with how to address the poverty, how to channel the anger, and how to join these new political struggles.

While rebellions in cities emerged and violence ensued, King dedicated what would be the final years of his life to the issue that dogged so many Blacks: poverty. He also strove to understand the sentiment of deep anger in many Black young people; and tried to empathize with their hurt while re-orientating them away from violence. This would become the work of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. until the moment of his tragic passing.

The Notorious B.I.G. certainly did not engage in the same work that Dr. King did. He did not live in King’s time. He was no political leader, no community organizer. Yet what ties him to King is Biggie’s place in the historical progression of African-American life. Biggie is apart of Bakari Kitwana’s “Hip-Hop Generation:” the one’s who come after the Civil Rights/Black Power struggle and inherit the world those movements left behind. What Biggie becomes, is this generation’s artistic icon; he ascends into a cultural hero.

As King represents the best in humanity and the quintessential symbol for a generation, B.I.G. serves as one generation’s definition of what a rapper should be and its most poignant example of success. And like W.E.B DuBois is forever linked with Booker T. Washington, or Martin Luther King with Malcolm X, Biggie is forever tied with the other defining luminary of his time—Tupac Shakur.

B.I.G.’s discussion of urban narratives, his poetic creations of imagined situations, and his story’s unique ability to resonate with the sentiments and conditions of a time, mirrors what we love and adore with so many of our artistic figures: the Odetta’s, Bob Marleys, Chuck D’s, Richard Wright’s, and Zora Neale Hurston’s of our culture.

There is no doubt that many of the stories which come forth from Biggie are disturbing, horrifying, and troubling. The “bitches,” “hoes,” guns, robberies, "stick-up kids," misogyny, crack sales, and patriarchy which these stories detail indeed are…difficult. Nor are the sentiments of “keeping it real,” “I write about what I see,” or “if she acts like a hoe then and Imma call her a hoe” valid—a culture that presents these explanations must be challenged, critiqued, and pushed.

But this is not the totality of Biggie’s work. The descriptions he provided indeed had truth in them. No doubt the behavior it associated with is problematic, but the presence of it is nothing new. No question violence, sexism, and drugs take a drastically different tone in present society. But pimping, hustling, and guns are not new. They certainly existed in Dr. King’s time. "Come on people," they even existed in Bill Cosby movies. Wallace took the alias of "Biggie Smalls" from the name of a gangster/hustler in Cosby and Sidney Poitier's 1975 movie Let's Do It Again.

The brilliance of the Notorious B.I.G., and of the Hip-Hop culture, is the point of view it provides. As Biggie put it, “from a young G’s perspective.”

The fact that Biggie could turned this perspective into a tool which enables him to reach financial success, this is what stands out to the Hip-Hop culture. Yes, it is absolutely steeped in capitalism’s excess, exploitation, and materialism. But for many people of color, it speaks to a truth and a desire. The work of changing what we desire, what we value, and what we want certainly is needed. If “money, hoes, and clothes is all a nigga knows,” then we have to expose that view to other ideas.

But it does not change the fact that it speaks to a generation, to a culture. Biggie Smalls speaks to the generation which lived through the crack epidemic, and to Hip-Hop culture. And what makes him their symbol is that... he is from it.

That is why Dr. King and The Notorious B.I.G. are celebrated. They represent something. They are of and apart of a community. The tie people have to them is not just marketed or mass-produced; the ability, talent, and work of these men tie us to them.

Their failures, flaws, and downsides are plentiful. They are problematic and complex. But such is life.

Regardless, these are our heroes.

R.I.P.

Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Christopher Wallace

Michael Partis

michaelpartis@gmail.com

www.michaelpartis.blogspot.com

myspace.com/hiphopthought

http://my.rawkus.com/profile/ForeThought

No comments:

Post a Comment