The South Bronx, and Public Housing.

The nomination of Judge Sonia Sotomayor has brought both places to the public’s frame of reference over the past few weeks. That reference is also drenched in a confluence of negative stigmas, connotations, and stereotypes. This has allowed the South Bronx and the projects to proliferate in marginalization and isolation. Poverty and social neglect are realities that this American society refuses to acknowledge. Accountability for the condition of these places turns into a discourse on personal responsibility.

But the potential of a Supreme Court Justice rising from these circumstances both complicates and fits this narrative. It complicates how we think of public housing and its residents – it is not a Black Hole for potential, but rather it can cultivate the best and the brightest…just like the rest of the United States. And in this way it still fits the story we love to hear: an “American Dream” where anybody can make it; the cream rises to the top; and if she did it, then you can do it. While the New York Times chose to affirm this trope (see the May 29th article “Up and Out of NY’s Projects), the Washington Post opted to posit Sotomayor’s Bronxdale Housing Projects in a more sobering light. Rather than it being a beacon of opportunity, they confront the stark trouble and problems which Bronxdale’s residents endure today—some of recent, many for over a generation. As Biggie once poignantly told us, “Things done changed…”

As a former resident of Bronx public housing, a life-long resident of the South Bronx, and a researcher on contemporary life in Bronx public housing, this has been a conversation that has profoundly affected me; professionally and personally.

In response to the evolving and intensifying discussion of these issues in many circles, I wrote the following letter as a reflection of my time and my experiences, and as a testament to the shared experience and group ethos me and many of my peers were a part of.

In that spirit I hope this letter is a catalyst for the public and for concerned citizens and residents to think deeply about poverty, isolation, and treatment in our society. And that is pushes us to social and political action that improves access, opportunity, and justice in every economic, material, and theoretical facet of our country.

In Struggle,

Michael Partis

-------------------------------------

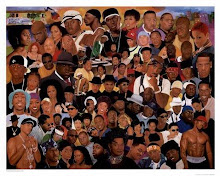

“Looking historically at Bronx public housing is quite jarring for someone who grew up there during the 90's. For seven years, I lived in the Castle Hill Projects. Moreover, a large amount of my friends are part of my peer group and came of age in NYC public housing: many in the Bronx (Mitchell, St. Mary's, Paterson, Edenwald, Soundview, Webster, Forest), and many in Harlem too (Polo Grounds, Wagner, Washington, Johnson, Taft).

We spent summers together in parks; winters in building hallways & stairwells. We tried to scam food stamps for real cash (before they turned them into EBT cards); played in basketball tournaments, drank Tropical Fantasy soda, and got into trouble. It wasn't deviant behavior or a culture of poverty. For us, it was life.

But for those like me who came up in the PJ's after the "Crack Era," the hood was the valley, the shadow, the death, and the Promised Land. No, it wasn't New Jack City. But drug dealing was unequivocally, unquestionably, the number one employer in the neighborhood. It certainly was partly ethos—in so many ways me, the friends I grew up with, and the people we all ran with, WANTED to hustle. Sure it was an easy economic opportunity. Nobody was paying to you work in their supermarket or bodega (immigrant adults did those jobs); nobody gave you a few dollars to sweep up hair at the barber shop; and "working class" families were few and far between. We weren't even in the working-class boat. Many of us lived on welfare; ate off Food Stamps; and grew up on WIC (all of this was before they started "Work-fare"). No doubt, some folks had disposable income from decent city or state jobs. But the rest of us were poor; like in poverty; like keeping the oven on to stay warm during the winter; making hot dogs and Chief Boyardee for dinner; and eating those terrible name brand knock-off WIC cereals for breakfast.

But a lot of us hustled because, it looked fly. It was cultural—not just an aesthetic, but also social capital. It built your street cred; built your name. It opened up business opportunities: you could expand your hustle to other buildings, down the street, and (if you were ready for war) other neighborhoods. And the younger you started, the better you could get. The hungrier you are; the greater your hustler's ambition; and the sooner you started stacking, you could make money and "get out."

Some people call it crime. We called it a dream. For us, it was our promise land.

Of course not everyone looked to this way out. But I'll refrain from going into the success stories of those who don't go this route. Sure you can overcome the poverty, and inequality, and become a Supreme Court nominee or a college graduate. But it doesn't mean the game should be set up that way...or that everyone can win.

This isn't a Donald Goines book, or a Terri Woods publication. It's not a screenplay written by the Hughes Brothers, or on set on some project bench. It's a story lived by many, embodied in many, and familiar to too many.

Scary thing is that this is the experiential for not just project kids, this is the experience for many U.S. kids who grow up Black and in poverty. And it's not just a 90's thing or a 2000's thing. You still see it in the Bronx to this day. You go walk through Edenwald today; visit Watson Ave or Colgate Ave; check out Soundview; travel around Mount Eden tonight. Guns, drugs, and the lifestyle it inflicts on its participants and viewers is a frightening site.

Of course there is plenty of blame to go around (isn’t there always?). And everybody should hold some accountability. But someone has to take accountability for structural inequality; and the inequality in access, resources, and opportunity.

Who makes public policy with inefficient "solutions" to address long-existing social problems? I don't think anyone in 2175 Lacombe Avenue did; and I know no one in apartment 8I did for damn sure. And...maybe that's the problem right there.

But indeed this poignant viewpoint and insight is what led me to do a case-study of youth in Bronx public housing for my undergraduate Senior Thesis at Fordham University. It’s why I am continuing this research as an ethnography and dissertation in Graduate school. And why public housing, inequality, poverty, policy, and socio-economic structures are my research interest. Because maybe, if we can allow those experiencing this lived reality to bring their own stories to the center of our public conversations...then maybe America can see how ugly the persistence of racism and discrimination is. Or realize the ramifications of local level officials’ impotence, neglect, and unabashed self-interest (see the absolute MESS occurring in the New York State legislature currently). Or truly recognize the ineffectiveness market-based economic solutions have; and just how sinful and self-indulgent economic empowerment zones, corporate giving, and the entire reform platform have been.

So there goes a personal narrative on life in public housing by someone who lived it. From a Black man who was influenced by sports, drugs, and violence, but now is a Ph.D. student. And who hopes to allow others from related backgrounds, with similar stories, and a shared lived experience to speak about their lives in the Bronx projects for themselves.

Michael Partis

Castle Hill Projects 1992-1999.

The Hood 1986-Present.

Fordham University-Rose Hill B.A. 2008

CUNY Graduate Center Ph.D 2014”

------------

If anybody would like to read my Senior Thesis on young people in the South Bronx's Mitchel Projects, or interested in and/or does research on public housing in the United States, please feel free to contact with me at michaelpartis@gmail.com.

Peace