“Speak

What I Want, I Don’t Care How Ya’ll Feel”

Nas’

Untitled Album and the Consequences of Censorship on Cultural Expression

(I originally

published this article in The Coup Magazine’s September 2008 “Censorship issue. Reposting it to my blog, in light of all the recent discussion on the album's ghostwriters.)

“…So untitled it is

I never change nothin'

But people remember this

If Nas can't say it, think about these talented kids

With new ideas being told what they can and can't spit

I can't sit and watch it”

Nas-

“Hero”

Words have the power to express, advocate, share, and transform.

They exist in the abstract, in the realm of ideas. Yet they go beyond the

tangential because of their power to invoke and to inspire. Words may come in

all parts of speech, but their greatest relationship to us is how they all

function as verbs in our life. In living, words are action.

It is that very spirit that makes speech important; so important that it is the first right protected and ensured in the United States’ essential legal and organizational framework: The Constitution.

The controversy behind the title of rapper Nas’ ninth album pushes the greater public, the Hip-Hop community, and (most specifically) the socially-conscious members of the African Diaspora to examine how significant words are to societal ideas. They are asked to consider what censorship does to artistic expression that is rooted in cultural practice. How is art (and the artist) tied to social change?

In several interviews Nas cited his reason for naming his album Nigger was to create critical discussion on the term’s historical development, and how that relates to the variance in its contemporary usage. Subsequently, the album would highlight why the current usage has created oppositional, mutually-exclusive views on the word.

In an October 2007 interview with MTV News, Nas’ discussed what he felt was a rush judgment on the album, based on stereotypes associated with rappers. "If Cornel West was making an album called Nigger, they would know he's got something intellectual to say," he said. "To think I'm gonna say something that's not intellectual is calling me a nigger, and to be called a nigger by Jesse Jackson and the NAACP is counterproductive, counter-revolutionary."

Illuminated here is the challenge: to see Nas’ work in the proper context.

Is this attempt any different than Richard Wright’s or James Baldwin’s work of social fiction? What differentiates Nas’ album about the history of the word nigger from Kara Walker’s provocative artistic exploration of race relations, sexual practice, and gender politics? Would Nigger be more like The Lost Poets’ “Niggers Are Scared of Revolution,” or Harvard Law professor Randall Kennedy’s “Nigger: The Strange Career of a Troublesome Word?”

The deeper question though, is can an artistic treatise on the word Nigger produce social change?

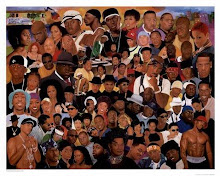

The artist’s role in political matters is a topic much discussed. One of their greatest powers is the ability to reach multitudes of people; they have a number fans, supporters, critics, and detractors as their audience. Hip-Hop artists are prime examples of this, as the culture has created music, art, fashion, and aesthetics that speak for the post-Civil Rights generations and for some of the most under-represented populations in America. Some Hip-Hop participants use this great stage as artistic license to create individual forms of expression that somehow speak for the under-represented. Some take the treads of political consciousness that are historically intrinsic to the legacy of the African Diaspora, and contemporary societal issues, to deliver social commentary.

Nas’ attempt to name his album Nigger tries to do all of these things. In fact it also highlights an important moment in Hip-Hop music.

While Hip-Hop contains a large range of perspectives and personalities, a stigmatized, stereotyped, misconstrued image of the culture is still pervasive in popular society. This image is produced partially by the immature, brash, sexist, vulgar nature of some Hip-Hop; and partially due to the one-dimensional, narrow, and judgmental view of conservative critics and older Black leaders (most notably those older Blacks who were leaders and participants in the Civil Rights movement) who reduce the complexity and breath of the art form to “hoes,” drugs, “bitches,” and…”niggas.”

Conversations around the “N-Word” often produce heated debates and divisive results. It shows an aspect of the Black community that fragments the group cohesion needed to address the large scale problems still faced almost forty years after the Civil Rights and Black Power movements.

This is what makes the Nigger album important: that it attempts to push the younger generation into a constructive discussion of the word by using the forum that speaks to a large number of its generation, and allows those older members of the community to revisit the complicated usage the word has in today’s youth culture. If seen in a broader scope, the album is a form of community organizing.

The challenge is to open the lens wide enough to understand this view.

In a May 2007 interview with PBS’s Bill Moyers, Princeton professor Melissa Harris-Lacewell spoke about the need to have a broad understanding of contemporary race relations and to embrace new ways to actively resist and change the inequality it causes. She asked that we re-examine our approach stating, “…I often say that Jim Crow, we could think of Jim Crow as a nail. And the protest against Jim Crow was a hammer. A hammer is an extremely effective tool when you're dealing with a nail...Contemporary racial inequality is a screw, and if you take a hammer and start pounding on a screw, you just end up with a mess which means we have to live with the fact that a new generation is going to have to innovate a screwdriver to deal with the new problem. And that screwdriver might not look anything like the hammer. And we can't keep yelling at them to use a hammer for a new problem.”

Hip-Hop artists arguably have the closest, most intimate connection with young people of color. Instead of suppressing the movement, perhaps there needs to be a more collective attempt to cultivate it. Maybe with more historical context taught and with more encouragement and mentorship from veterans of past movements the political potential of the culture can be tapped.

Maybe a Nas album that quotes James Baldwin, critiques Fox News, explores the hypocritical nature of American society, reflects on the possibility of a Black president, and expresses stories of racism, poverty, and struggle by young Black people has the power to inspire.

Can we afford to have the power to create, explore, and inspire suppressed?

What opportunity can censorship in this issue afford us?

It is that very spirit that makes speech important; so important that it is the first right protected and ensured in the United States’ essential legal and organizational framework: The Constitution.

The controversy behind the title of rapper Nas’ ninth album pushes the greater public, the Hip-Hop community, and (most specifically) the socially-conscious members of the African Diaspora to examine how significant words are to societal ideas. They are asked to consider what censorship does to artistic expression that is rooted in cultural practice. How is art (and the artist) tied to social change?

In several interviews Nas cited his reason for naming his album Nigger was to create critical discussion on the term’s historical development, and how that relates to the variance in its contemporary usage. Subsequently, the album would highlight why the current usage has created oppositional, mutually-exclusive views on the word.

In an October 2007 interview with MTV News, Nas’ discussed what he felt was a rush judgment on the album, based on stereotypes associated with rappers. "If Cornel West was making an album called Nigger, they would know he's got something intellectual to say," he said. "To think I'm gonna say something that's not intellectual is calling me a nigger, and to be called a nigger by Jesse Jackson and the NAACP is counterproductive, counter-revolutionary."

Illuminated here is the challenge: to see Nas’ work in the proper context.

Is this attempt any different than Richard Wright’s or James Baldwin’s work of social fiction? What differentiates Nas’ album about the history of the word nigger from Kara Walker’s provocative artistic exploration of race relations, sexual practice, and gender politics? Would Nigger be more like The Lost Poets’ “Niggers Are Scared of Revolution,” or Harvard Law professor Randall Kennedy’s “Nigger: The Strange Career of a Troublesome Word?”

The deeper question though, is can an artistic treatise on the word Nigger produce social change?

The artist’s role in political matters is a topic much discussed. One of their greatest powers is the ability to reach multitudes of people; they have a number fans, supporters, critics, and detractors as their audience. Hip-Hop artists are prime examples of this, as the culture has created music, art, fashion, and aesthetics that speak for the post-Civil Rights generations and for some of the most under-represented populations in America. Some Hip-Hop participants use this great stage as artistic license to create individual forms of expression that somehow speak for the under-represented. Some take the treads of political consciousness that are historically intrinsic to the legacy of the African Diaspora, and contemporary societal issues, to deliver social commentary.

Nas’ attempt to name his album Nigger tries to do all of these things. In fact it also highlights an important moment in Hip-Hop music.

While Hip-Hop contains a large range of perspectives and personalities, a stigmatized, stereotyped, misconstrued image of the culture is still pervasive in popular society. This image is produced partially by the immature, brash, sexist, vulgar nature of some Hip-Hop; and partially due to the one-dimensional, narrow, and judgmental view of conservative critics and older Black leaders (most notably those older Blacks who were leaders and participants in the Civil Rights movement) who reduce the complexity and breath of the art form to “hoes,” drugs, “bitches,” and…”niggas.”

Conversations around the “N-Word” often produce heated debates and divisive results. It shows an aspect of the Black community that fragments the group cohesion needed to address the large scale problems still faced almost forty years after the Civil Rights and Black Power movements.

This is what makes the Nigger album important: that it attempts to push the younger generation into a constructive discussion of the word by using the forum that speaks to a large number of its generation, and allows those older members of the community to revisit the complicated usage the word has in today’s youth culture. If seen in a broader scope, the album is a form of community organizing.

The challenge is to open the lens wide enough to understand this view.

In a May 2007 interview with PBS’s Bill Moyers, Princeton professor Melissa Harris-Lacewell spoke about the need to have a broad understanding of contemporary race relations and to embrace new ways to actively resist and change the inequality it causes. She asked that we re-examine our approach stating, “…I often say that Jim Crow, we could think of Jim Crow as a nail. And the protest against Jim Crow was a hammer. A hammer is an extremely effective tool when you're dealing with a nail...Contemporary racial inequality is a screw, and if you take a hammer and start pounding on a screw, you just end up with a mess which means we have to live with the fact that a new generation is going to have to innovate a screwdriver to deal with the new problem. And that screwdriver might not look anything like the hammer. And we can't keep yelling at them to use a hammer for a new problem.”

Hip-Hop artists arguably have the closest, most intimate connection with young people of color. Instead of suppressing the movement, perhaps there needs to be a more collective attempt to cultivate it. Maybe with more historical context taught and with more encouragement and mentorship from veterans of past movements the political potential of the culture can be tapped.

Maybe a Nas album that quotes James Baldwin, critiques Fox News, explores the hypocritical nature of American society, reflects on the possibility of a Black president, and expresses stories of racism, poverty, and struggle by young Black people has the power to inspire.

Can we afford to have the power to create, explore, and inspire suppressed?

What opportunity can censorship in this issue afford us?

By Michael Partis

@ The Coup Magazine